MAGIC MENTOR MONDAY: Charles Bertram

October 12, 2015

Welcome to MAGIC MENTOR MONDAY. In this weekly series, I introduce you to my magic mentors – people who have inspired me to become a better magician. Each Monday you’ll meet someone who has offered advice, or acted by example, to help steer my career.

Some of these people are alive, others no longer with us. Some are famous, others not so much. The beauty of mentorship is that you don’t necessarily have to meet your mentor face-to-face, nor even live during the same time in history. Many of the people who motivated me were alive a century before I was born! By reading classic books, old newspapers, and magazine articles, I’ve tracked down stories about their lives and work that continue to inspire me to become a better entertainer.

My “big three” mentors are Max Malini, Johann Nepomuk Hofzinser, and Jean Eugene Robert-Houdin. Each of these giants will be featured in coming weeks. You’ll also read about more contemporary figures like Harry Lorayne and Albert Goshman, non-magicians Danny Kaye and Sammy Davis, Jr. and even fictional characters like Willy Wonka.

How do mentors inspire? They set examples, helping us imagine how we too might solve a particular problem. By seeing the world through a mentor’s lens, we can learn more about them, and about ourselves, at the same time.

This week we’ll focus on the Court Conjurer:

CHARLES BERTRAM (1855-1907)

British magician Charles Bertram was one of the first to educate fashionable society that conjuring could fascinate sophisticated adults. He showed them that “a conjurer was not necessarily an uneducated, ill-dressed, and unreliable person, who preferred to come in at the back-door and take supper with the servants, but might be a gentleman who could hold his own in any company, who would not disgrace his host or hostess, and who could be relied on to amuse and interest their guests.” (Sidney Clarke in The Annals of Conjuring)

There is no evidence that Bertram ever met the subject of last week’s column, Max Malini, despite the fact that Bertram and Malini both entertained a similar clientele.

During his career, Charles Bertram was dubbed “The Court Conjurer” and was invited to perform in the Royal household no fewer than twenty-two times.

Picture this:

You are a guest at an elegant dinner party in Victorian London. After a satisfying meal served on fine bone China by white-gloved butlers, your host invites you to retreat to the drawing room. He offers cigars and cognac, and tells you to make yourself comfortable. It’s time for a private entertainment by Charles Bertram the magician.

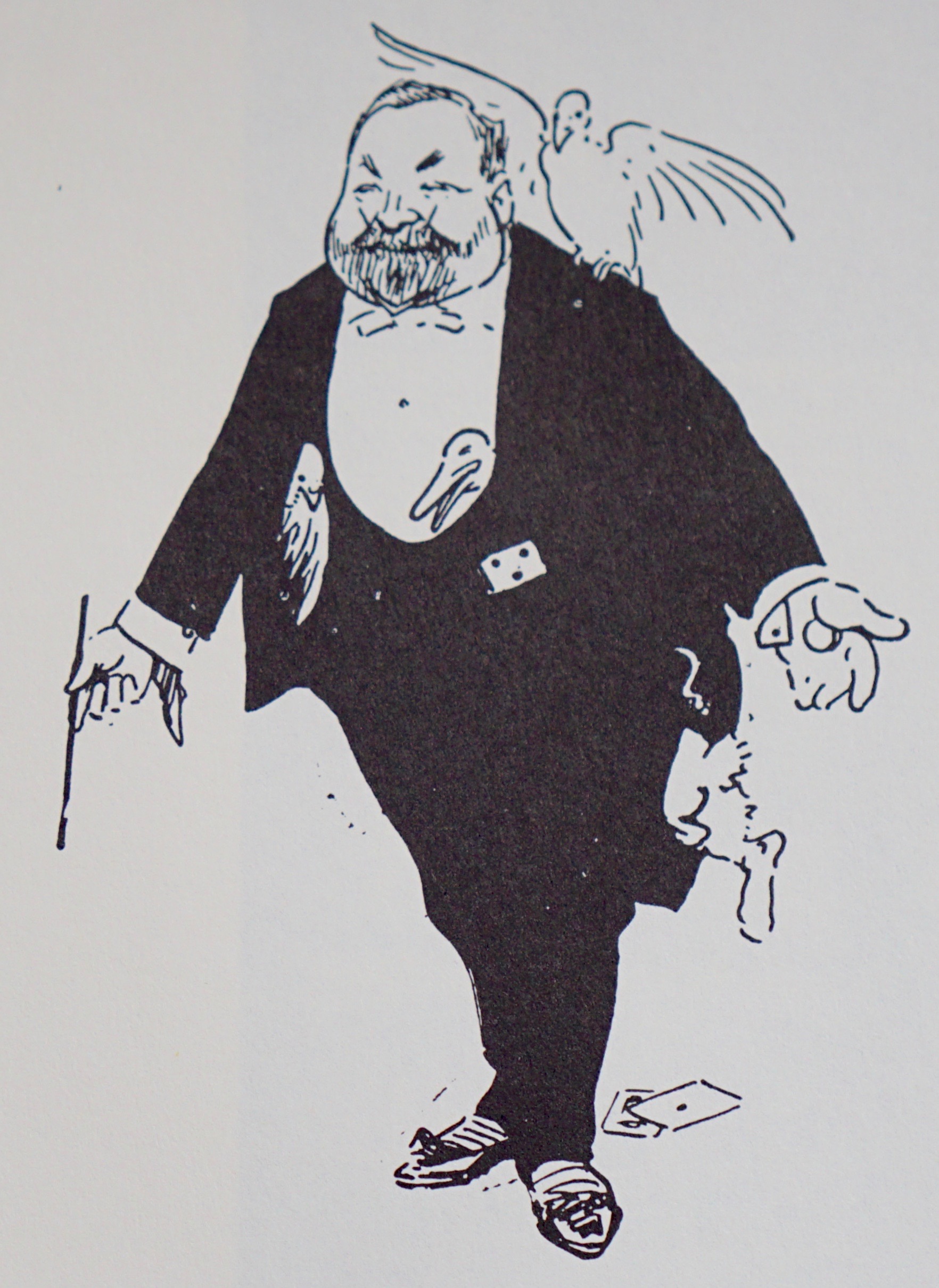

Bertram walks out from behind a handsome folding screen, a jolly looking man in a well-tailored tuxedo. He sports a closely-cut and pointed beard and waxed moustache. He holds a small birdcage containing a live canary, ready to perform the now-classic Vanishing Birdcage trick. Drawing attention to the canary, Bertram comments that distinguished and sensitive audiences, “such as yourselves,” may be concerned with the safety of the animal. He swings opens the cage door to show that the bird is alive and well. At that moment, however, the bird hops out of the cage, and flies out of the room. Bertram responds, “You have flown away, have you? Well take your cage with you!” He tosses his arms upward and vanishes the birdcage in the usual way.

In my opinion this presentation is brilliantly constructed. The bird was meant to fly away all along, but Bertram made it appear unpremeditated. The audience was eager to see how the magician would resolve this awkward predicament. It was no longer just a trick, but a problem-solving exercise: “How is he going to get out of this?” they wondered. By acting convincingly, as if the vanishing birdcage was an ad-libbed solution, he spurred the audience to react with even stronger applause. In their minds, they saw an artist at work, which is considerably more interesting than a pat piece of “material.”

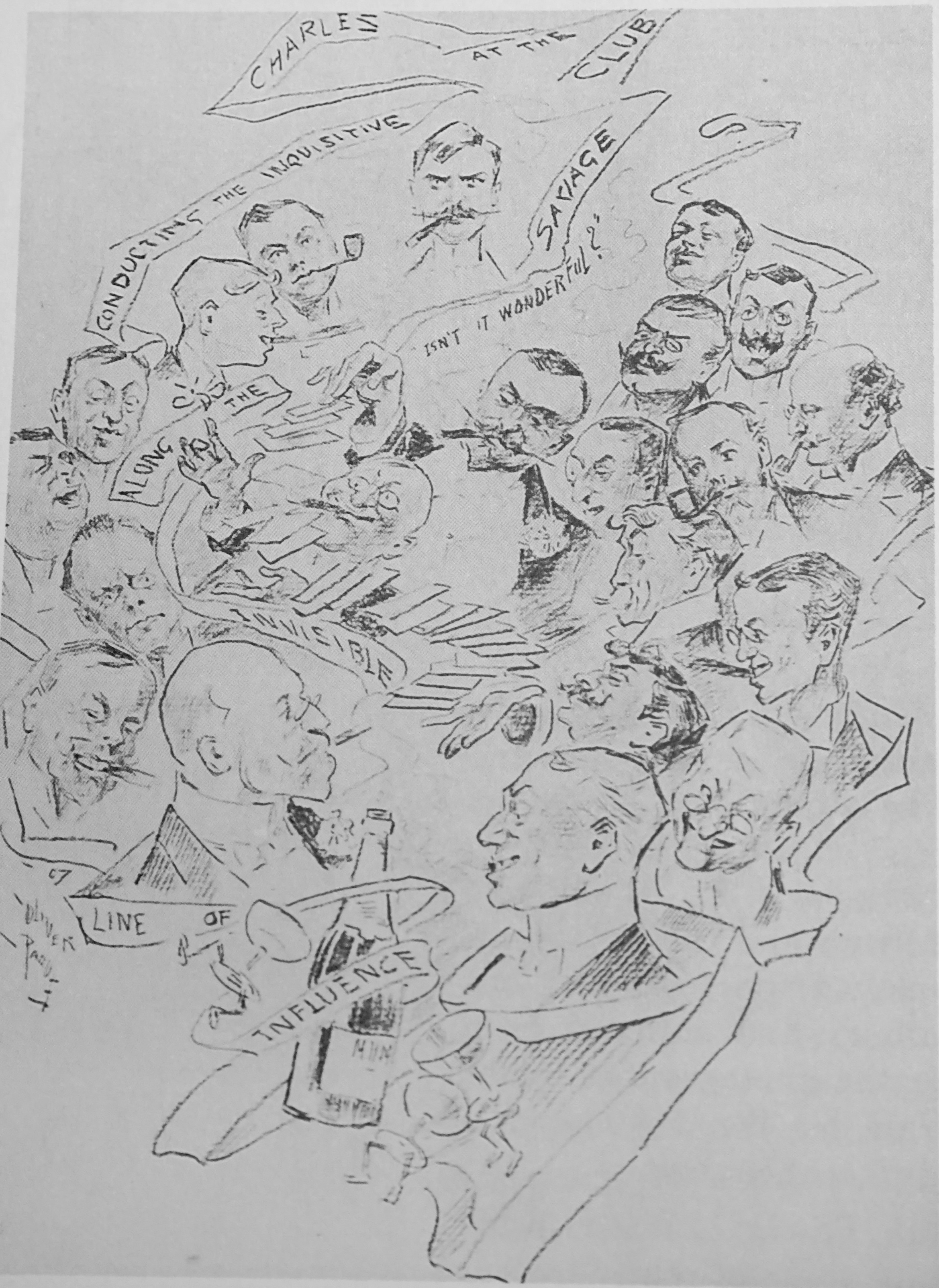

“Charles at the Savage Club conducting the inquisitive along the invisible line of influence,” 1907 (Peter Lane Collection)

What lessons have I learned from Charles Bertram?

SOCIALIZE WITH CLIENTS

Charles Bertram became a member of two fraternal organizations, the Freemasons and the Savage Club, rubbing elbows with politicians, socialites, and military leaders. He socialized with powerful figures in London, and became very much in demand to perform at their elite dinners and social events.

Bertram learned to navigate what could be termed “the invisible line of influence” among members of high society. By becoming a member of a social club, he was no longer considered hired help. He was an insider, a trusted friend, “one of us.” He took advantage of his flourishing friendships and discovered that there was a great deal of money to be made by performing at private engagements gained through personal connections.

BE EASY TO WORK WITH

Charles Bertram did not require much from his hostess. From the hostess’ point of view, there was no need to turn her drawing room “upside-down.” Bertram only required a table, a chair, and a folding screen to store his props behind.

Taking this to heart, I try to make it easy for my private clients to work with me. Event hosts often experience a great level of stress on the day of their event, and I don’t want to add to that. Many weeks in advance, I send my requirements in a clearly-written rider, attached to my contract. In this way, the client has plenty of time to clarify any concerns. We’ve already discussed the room layout, my start time, the sound system, and lighting. By the time I arrive at the show venue, we simply carry out the plan. I like to say to the person who hired me, “Relax and leave it to me. Everything is taken care of.”

PERFORM ONLY “CLOSERS”

Bertram performed classic routines, and embellished them with jovial presentations that suited his personality. These tricks included: Conus Aces, Cups and Balls, Cards to Pocket, Diminishing Cards, Multiplying Billiard Balls, and the Miser’s Dream, among others.

He began each show with these familiar classics, and gradually stepped up his game by performing exponentially more impressive routines – items that could each close the show in its own right. For instance, Bertram vanished a couple of borrowed finger rings, followed by a walnut, an egg, and a lemon. He then displayed a coconut to the audience, cracked it open and discovered the lemon inside. He peeled the lemon and showed that it contained the egg. Cracking the egg, he displayed the walnut inside. Finally he cracked open the walnut and produced the two borrowed rings.

He began each show with these familiar classics, and gradually stepped up his game by performing exponentially more impressive routines – items that could each close the show in its own right. For instance, Bertram vanished a couple of borrowed finger rings, followed by a walnut, an egg, and a lemon. He then displayed a coconut to the audience, cracked it open and discovered the lemon inside. He peeled the lemon and showed that it contained the egg. Cracking the egg, he displayed the walnut inside. Finally he cracked open the walnut and produced the two borrowed rings.

As amazing as this trick is, it was not his closer. Later in the same program he performed “The Favors of Bacchus,” pouring different wines and liquors from a clear glass decanter. He filled glass after glass with different alcoholic beverages for his audience, and passed them out for people to taste. Bertram observed, “This is a very pretty trick and causes great astonishment.” I have personally performed my own version of both of these tricks, and heartily agree with Bertram’s assessment.

Since I personally represent “magic” during the course of my show, it’s my responsibility to present the most powerful material possible. I select my material so that each item could, if necessary, be the show’s closer. I am extremely picky when adding a new routine to the show. It must pass a filter I call the earthquake test: if there were an earthquake and everyone had to evacuate the show early, would this routine have been strong enough to be my closer?

The challenge is to take the strongest material and organize those elements into a longer routine that has its own internal dramatic structure. The show has to build in a pleasing arc, or else there is only one “note” that will eventually wear off.

MAKE A PRINTED PROGRAM

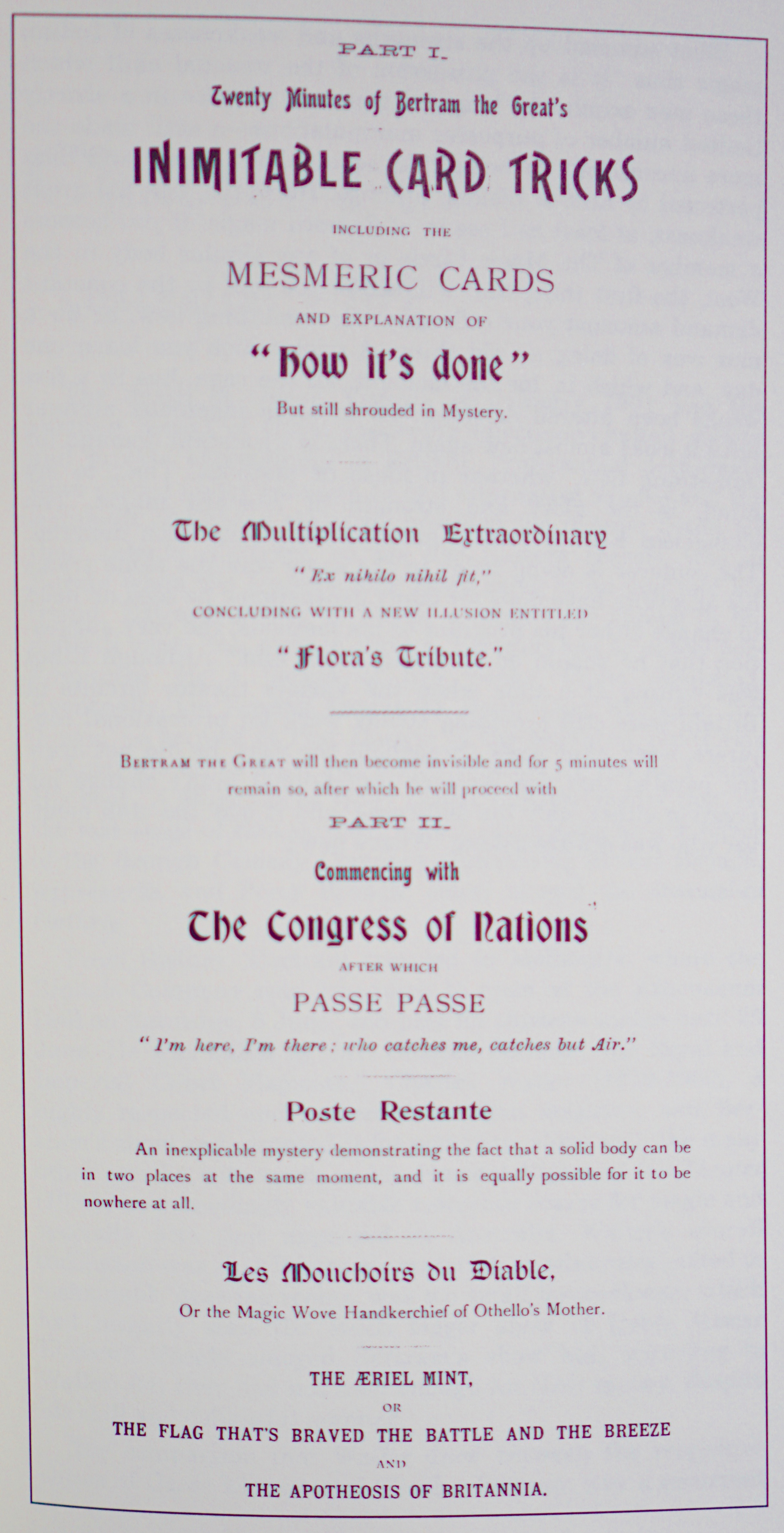

In an effort to expand his reach to larger audiences, Bertram presented public shows in mid-sized theaters across England, India and North America. The shows ran about one hour long, plus an intermission. Upon entering the theater, audience members received a printed program containing the title of each act.

Here is sample of one Bertram program:

I’ve discussed the idea of distributing a show program with other professional magicians. Most dislike the idea. They feel that having a printed program prevents flexibility and experimentation from show to show. If you don’t follow the program, they argue, it becomes apparent to the audience that your set list doesn’t match up with the show they are watching.

While I understand this argument, I follow Bertram’s approach. Chamber Magic customers receive a printed list of the show contents on their chairs, similar to the playbill you would receive at a classical music concert or Broadway show. During the show, some of my patrons refer to the program, looking down at the end of each trick to see what’s next. Others like to have a concrete reminder that helps jog their memory upon returning home.

Of course I don’t want my performances to stagnate. I can always include or replace items on the program at my own discretion. If an audience member asks about it later, I simply say with a wink, “I cooked something off-the-menu for you tonight.”

Conclusion

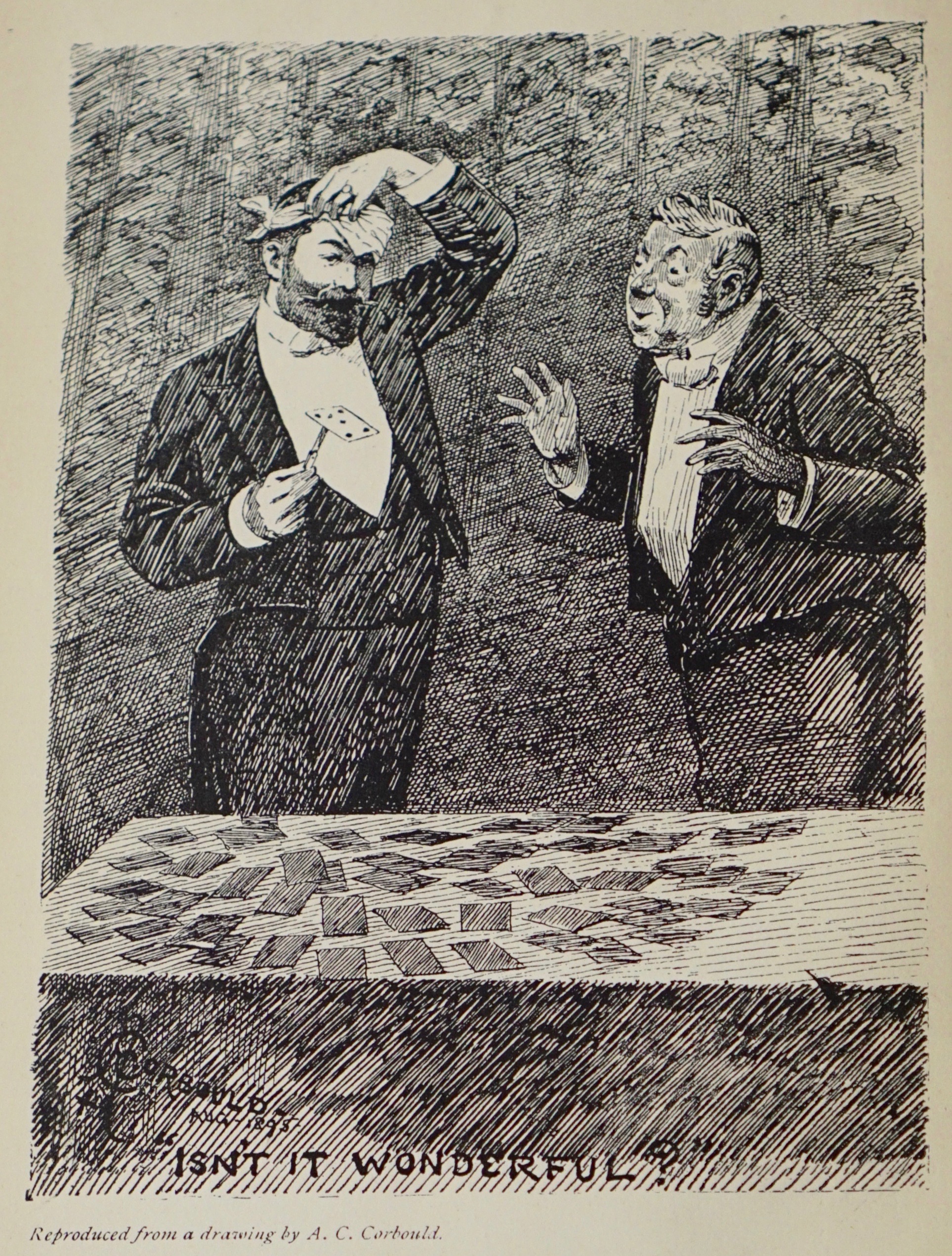

One of the things that first drew me to learn more about Charles Bertram was his catch phrase. At the end of each mind-blowing trick, Bertram softened the blow by uttering the phrase, “Isn’t it wonderful?”

One of the things that first drew me to learn more about Charles Bertram was his catch phrase. At the end of each mind-blowing trick, Bertram softened the blow by uttering the phrase, “Isn’t it wonderful?”

I find this phrase to be a lovely and endearing way to frame a magic trick. “Isn’t it wonderful?” takes the sting out of being fooled. It elevates the trick beyond being a mere puzzle, and subtly reminds the audience to focus on how it makes them feel. Bertram’s tricks were good enough that they truly filled the audience with wonder.

Next week: JOHANN NEPOMUK HOFZINSER

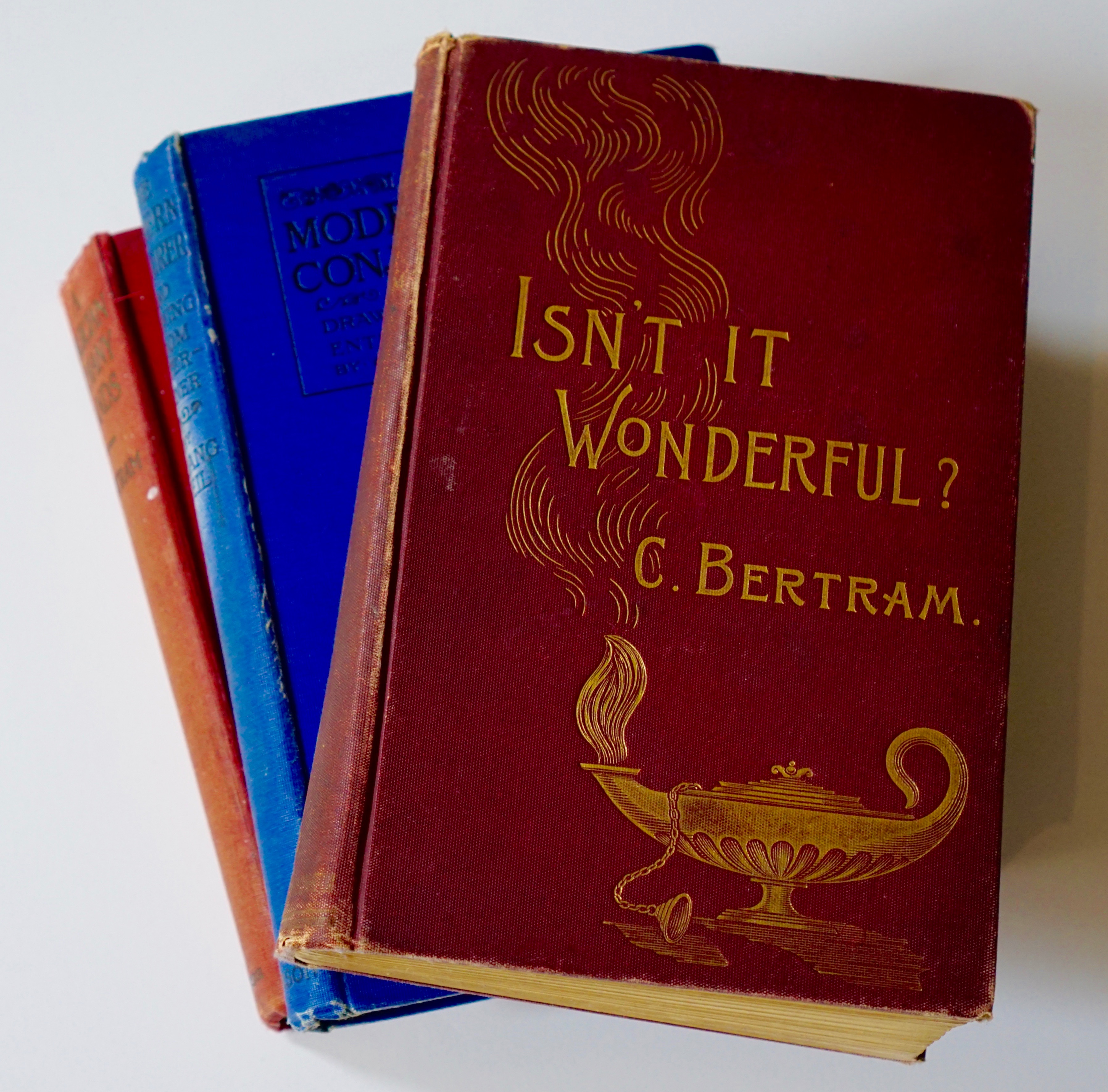

For further study, I recommend the following books and magazines.

- Charles Bertram The Court Conjurer, by Edwin Dawes

- Isn’t It Wonderful, by Charles Bertram, 1896

- A Magician in Many Lands, by Charles Bertram, 1896

- The Modern Conjurer and Drawing Room Entertainer, by C. Lang Neil, 1903

- The Annals of Conjuring, by Sidney W. Clark, Chapter 11