Review of new Max Malini book in The Magic Circular

July 6, 2022

THE MAGIC CIRCULAR, official magazine of The Magic Circle, London

July 2022 issue

Book reviewed by Bob Gill

‘Chutzpah’ is from Aramaic, meaning audacity bordering on the irresponsible. In traditional cultures it was a word of rebuke, while in more modern times it has come to carry with it a tinge of admiration. It is the term one constantly returns to when attempting to encapsulate the subject of this hefty book, the living embodiment of the word.

Max Malini was that entity who still stands today as a true one-off; there has not been his like since his demise in 1942 at the age of 69, which in a collective of copyists is something to behold. That’s not to say Malini’s reach was not extensive, but none was so completely under Malini’s spell than the author of this love story to him. For it wasn’t just Malini’s routines Mr Cohen seized upon; it was his entire ethos as the high- society magician of his time. So it seems entirely apposite that it is Cohen who pens this tribute; veneration permeates every fibre of the pages in this tome.

In the meantime Dai Vernon and Charlie Miller continued to heap praise upon Malini in their columns in Genii. Vernon was particularly taken with how spontaneous Malini made all his magic seem. In that respect Malini was ahead of his time; no stagey coloured boxes or tubes beloved of that era, no props at all other than the articles Malini borrowed or ‘found’ on site. Vernon loved that Malini would go to such effort to engineer his effects, staying at least one step ahead; for example, he’d note what coinage was included in the change a punter would receive at the bar, so he knew what coins he had in his pocket, and make full use of that knowledge.

The author’s fascination with Malini began when he read Ricky Jay’s Learned Pigs and Fireproof Women (1986). This prompted him to seek out Malini references wherever he could, and he made a point of collecting information about this continuously itinerant performer. The result is a rich collection, three- quarters devoted to Malini’s magic, the remainder to his life and some larger-than-life stories about the Napoleon of Magic.

The first part of the book explores Malini’s life. It is more anecdotage than biography, since it appears that even the diligent Mr Cohen could not nail all the fine detail. Malini is one of those figures, like Churchill, whom one pictures as a man of mature years, and there are scarcely any photos of him, even in this lengthy homage, as a young man. What we do get presented with in abundance are colourful yarns, and this makes the biographical section of this tome an easy read.

For the record, Max Breit was born in 1873 [editor note: 1875] in the village of Ostrov on the Polish/Hungarian border. Breit came under the spell of Frank Seiden, a magician, fire-eater and ventriloquist who kept a drinking saloon on the Bowery and showed him some simple sleight of hand. As a busker and saloon entertainer Malini would walk into a bar, loudly make himself known by the name that he had chosen to adopt, in his guttural, heavily accented growl, before performing with articles readily available in the hostelry: knives, glasses, glasses, matches, hats and playing cards. His magic was simple in plot and bold in execution. An early associate and influence was Emile Jarrow, who likewise used his deep Polish accent to add colour to his patter.

It is an interesting dichotomy that Max earned his spurs in the decidedly low-class saloon bars of those areas in New York where one feared to walk alone after hours. At some point Max Breit transitioned from selling matchbooks in lowly bars ankle-deep in spittoons and sawdust, through worldly barroom troubadour to become the overdressed dandy Max Malini who, dripping with medals and aiguillette, every inch the opera star or theatrical impresario, would perform exclusively for the wealthy and esteemed in chambers cushioned by the deepest pile carpet, in the process becoming one of the most publicised close-up workers the world has ever seen.

The transition began at the age of 29 when he tore the button from US Senator Hanna’s jacket and then magically restored it. Malini had the ability and bearing to impress people and command attention; the day after his button display he was performing for the then President of the United States. Thereafter he didn’t trouble the backstreet hostelries any further; he spent much of his life on his travels plying his well- paid trade on steam ships, luxury trains, five-star hotels, private mansions and palaces around the world. This was all at odds with the lot of the contented family man, a part of his life touched on in this book. He was, however, close to his son Oziar, who shared the stage with him as a child magician and went on to cover for Malini when he’d be increasingly indisposed in later years.

Of course, Malini’s encounter with that Senator was far from spontaneous; it was an opportunity that Malini prepared for and knowingly made the most of. This studied readiness for apparent spontaneity was a ploy Malini would use time and again, a trait best captured in Mr Cohen’s chapter “Chutzpah: Tales of Boldness”, which brings Malini’s unique personality to life through many diverting anecdotes. These include examples not just related to magic, the loading of a duplicate card into a spectator’s hat under great misdirection, for example, but talking an art dealer into giving him a valuable sculpture, one of only a pair in existence.

One area in which he was ahead of his time was self-promotion. Like Harry Houdini, he realised the power of the press early in his career, and he handled the Fourth Estate adroitly. The book gives countless examples of stories that were written about Malini. As so much of Cohen’s research was gained from press articles, we get to see them first-hand; as magicians we realise how many of them fall into the ‘too good to be true’ camp, but they make fascinating reading nonetheless, as the reader comes to realise how he gradually, inexorably built the legend of Max Malini as the hacks added to the stories to justify their by-lines. Every time he performed this must have put Malini under a degree of pressure to live up to these high expectations, but with this number of effects at his beck and call – around a hundred in these multitudinous pages – he had no such problem.

The abiding lesson from this wealth of descriptions, particularly those in the press, is how Malini would routinely take the simplest trick and make it a memorable mystery. His performances were framed in such a way as to infiltrate them into the spectator’s mind, like some kind of magical earworm, and remain there, to be extracted and retold, inflated with suitable augmentations in the telling that only added to the legend. He had the chops, despite his famously tiny hands, and armed with these he applied them in unforgettable ways. Cohen examines Malini’s techniques in some detail, particularly those with cards, most of which he made his own in idiosyncratic handlings. You’ll find here his quirky way with many of the standards: peeks, passes, top change, steals, colour changes, forces, and palms. He used his chops to deliver punches that still resonate in the repertoires of close-uppers today: “Card to Mouth,” “Universal/General Card,” “Card on Chair” and “Card on Wall or Ceiling.” He imbued these classics with a great sense of theatre, such that they became important performance pieces rather than magic tricks.

Malini’s trademark effects are probably, for most readers with even a fleeting awareness, “The Ice/Brick Under Hat,” “Biting A Button” and “The Malini Egg Bag.” With these standards Cohen does not disappoint, and he explores in some considerable detail not only how Malini performed them, but how the reader might learn to perform them him-or her-self. Arguably the trick that became forever associated with Malini was the production of a block of ice from beneath the hat he, or a participant, was wearing. Of course Malini was by no means the first to use a large surprise production to close a trick, but it was the choice of that improbable object that showed his mastery of the psychology of wonderment. His audiences were well aware of how a hefty block of ice is heavy, extremely awkward to handle, messy – and would surely have melted away if it was secreted on his body in a warm room. Slightly less spectacular, but still astonishing, was the production of a large, unruly, messy house brick, still with shards of mortar clinging to its sides, that Malini preferred to produce, reserving the ice for special occasions.

Intriguingly, and perversely perhaps, Malini did not publish details of his Egg Bag handlings (of which he had several, including one with an unfaked bag) but his methodology is laid bare by a guy called David Alexander (no, me neither) who made a study of various handlings employed by Malini, as well as that of Charlie Miller (which heavily informed the handling popularised by Ken Brooke in the 1970s).

One of the most valuable attributes Cohen brings to this work is the time he spent studying the stand-out routines for inclusion in his own programme, which adds an intrinsic practicality to his descriptions: they are truly authentic. The one that most tickled me was how they both went about transporting a selected card into the tailor-sewn lining of a volunteer’s jacket, a masterpiece of detailed planning, cunning and execution.

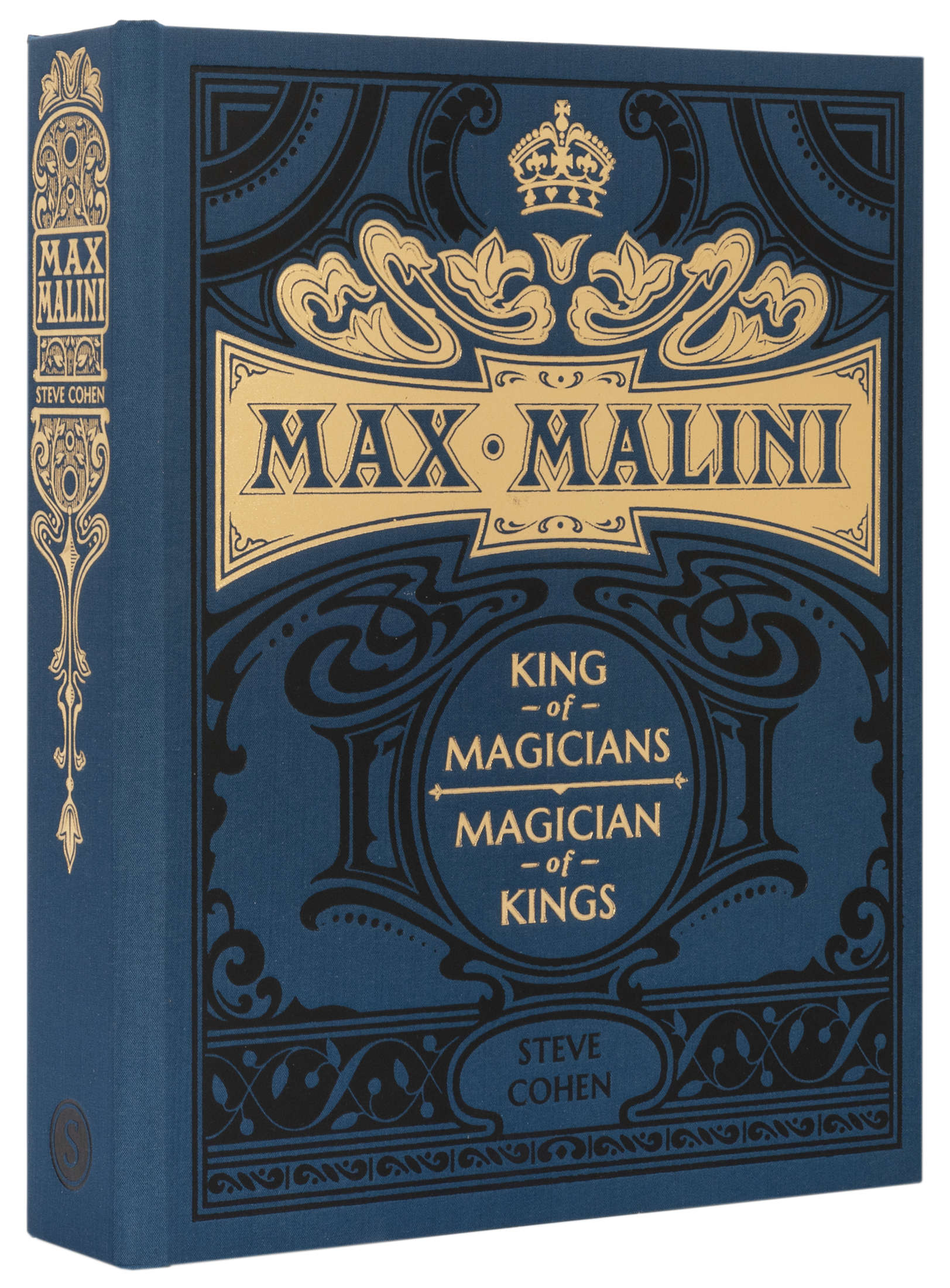

A welcome attribute that marks this out as the work of a true fanboy is the number of photos and memorabilia included within these ample pages, many from Cohen’s own collection: an invaluable resource of Malini’s timeline and his media references, and a diligent feat of research. It exemplifies the thoroughness of Cohen’s labours, which make this the authoritative book about one of magic’s more colourful characters and self- publicists.

Read this impressive labour of love to discover what all the fuss was about, and how prescient Max Malini was in his whole approach to performance: a very modern magician well ahead of his time in so many ways, who has much to teach us all. Along the way you also learn a great deal about Steve Cohen, itself no bad thing given the scale of his own achievement in the framing of magic performance. Give thanks for his passion bordering on obsession, his indomitable detective work, and his ability to bring the whole story alive.